My childhood feels like a distant film playing behind a dirty pane of glass—most of it smudged and unclear, except for the parts that still sting.

Those moments stand out sharply, not because they were joyful, but because they hurt the most.

I can’t recall my father’s face. He left before I could form a memory, disappearing when I was just a baby. All I’ve ever had of him is his name printed on my birth certificate.

That’s the extent of my connection to the man who vanished without a trace, leaving behind only questions.

“Your daddy went away,” my mom used to say. “Sometimes people just go away, Stacey.” I didn’t understand what she meant back then. I do now.

My mother, Melissa, wasn’t absent, but I often wished she had been. She was present in the worst ways: her anger, her exhaustion, her resentment.

Our small, dingy house always smelled of something burned or stale, and it echoed with raised voices and sharp silences.

Instead of bedtime stories, I remember slammed cabinet doors and the hum of the microwave heating frozen dinners while Mom muttered to herself, “I can’t keep doing this.”

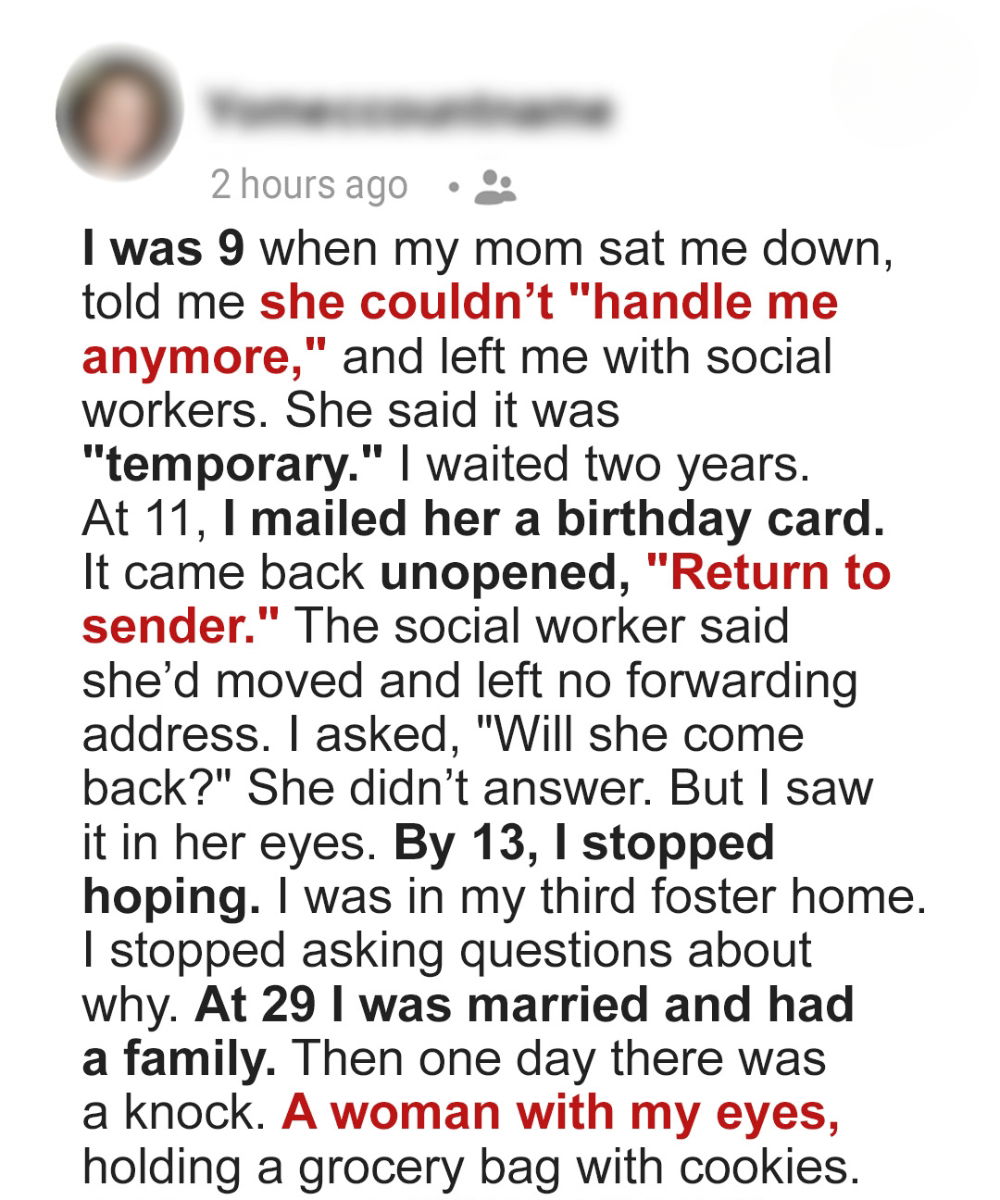

I was nine when everything changed.

It was a Friday, and I’d come home excited after acing a spelling test. But when I walked in, Mom sat at the kitchen table, surrounded by papers and shadows under her eyes.

“Stacey, sit down,” she said, not even glancing at me.

“I got a hundred on my test!” I announced, hoping for a rare smile.

But she didn’t smile. “I can’t take care of you anymore,” she said.

She slid a paper toward me. I couldn’t read much, but the word “custody” stood out. “Social services will be here tomorrow.”

I started crying. “I don’t want to go!”

“It’s just for now,” she said, eyes focused on anything but me. “Just until I get back on my feet.”

The next morning, Mrs. Patterson showed up with soft-spoken, kind eyes.

I clung to my mother, but she handed me a trash bag of clothes and said, “Be good. I’ll see you soon.”

I believed her.

The children’s home was big, cold, and loud. I shared a room with a quiet girl who barely spoke. Every day, I asked, “When is my mom coming back?”

“Soon,” Mrs. Patterson would say.

That word became my lifeline.

I told everyone she was coming soon. My mom loved me. She was just struggling. She’d come back.

At 11, I saved up to send her a birthday card. It came back stamped, “Return to Sender.”

Mrs. Patterson hugged me when I cried, but I saw the truth in her eyes. My mother was gone. For good.

By 13, I stopped asking about her. I was in my third foster home and had learned that hope was a dangerous thing.

It made you expect love where there was none. So I became invisible—quiet, helpful, forgettable.

Years passed. I grew up, graduated, and eventually found peace in my own little family. At 27, I gave birth to my daughter, Emma.

The moment I held her, I made a promise: she would never feel the way I did. She would always feel wanted, seen, and loved.

My husband, Jake, and I built a life that felt like healing. We bought a cozy home, took vacations, celebrated holidays, and filled the walls with pictures of joy. Emma’s laughter became my soundtrack.

“You’re such a good mom,” Jake would say.

“I’m trying,” I’d reply. Because I didn’t have a blueprint—I was building a home from scratch, using only love.

And then, one ordinary evening, everything shifted.

Emma had just gone to sleep. Jake was working late. I was sipping tea when a knock came at the door.

Standing on my porch was a frail, older woman clutching a grocery bag. Her hair was gray, her clothes worn.

But it was her eyes that caught me. They were mine. Or rather, hers—the mother who’d left me behind.

“I need help,” she said. “I’m homeless. I have no one. You’re my only child.”

I stood frozen, the warmth of my house suddenly distant.

She didn’t ask how I was. Didn’t ask about Emma or Jake. She just stood there like I owed her something.

I should’ve shut the door. But I didn’t. I let her in.

She slept on the couch, then moved to the guest room. Days became weeks. At first, she was polite, but then came the comments.

“I had no help when I was your age.”

“You were always crying. Always needy.”

And finally, the last straw: I overheard her telling Emma, “Sometimes you have to step away from people who hurt you—even family.”

Emma looked confused. I saw fear flicker across her face.

That night, I packed a garbage bag—just like the one she gave me as a child—and set it by the door.

“You have to leave,” I said.

“You can’t do this,” she gasped. “I’m your mother!”

“No,” I said. “You’re a stranger who left a child and only returned when you needed something.”

“Family is all you have!”

“No. Love is. And you gave that up a long time ago.”

After she left, I sat by Emma’s bed, watching her sleep, and promised again to never let anyone hurt her, not even blood.

Weeks later, I sent my mother a birthday card. Blank. No return address.

Inside, just one line: “Sometimes you have to step back from people who hurt you.”

I don’t wonder if she understood.

Because now I understand something she never did: parenting isn’t about what you get—it’s about what you give.

And I’m giving Emma everything.

The cycle ends here. With me.